In a world where differences often seem to divide us, cultural diversity is a powerful reminder of the beauty that can be found in our unique traditions, customs, and experiences. From the "Kalka" prints on Indian saris to the "Girih" patterns on Islamic architecture, cultural diversity is a rich and intricate tapestry that weaves together the stories of humanity and history.

Cultural diversity is not just about celebrating our differences; it's also about learning from one another and growing as individuals. When we engage with people from different cultural backgrounds, we gain new perspectives, challenge our assumptions, and develop empathy and understanding.

As such, the significance of cultural traditions are an integral part of our shared human experiences. These traditions not only provide a sense of identity and belonging but also serve as a bridge between generations and cultures.

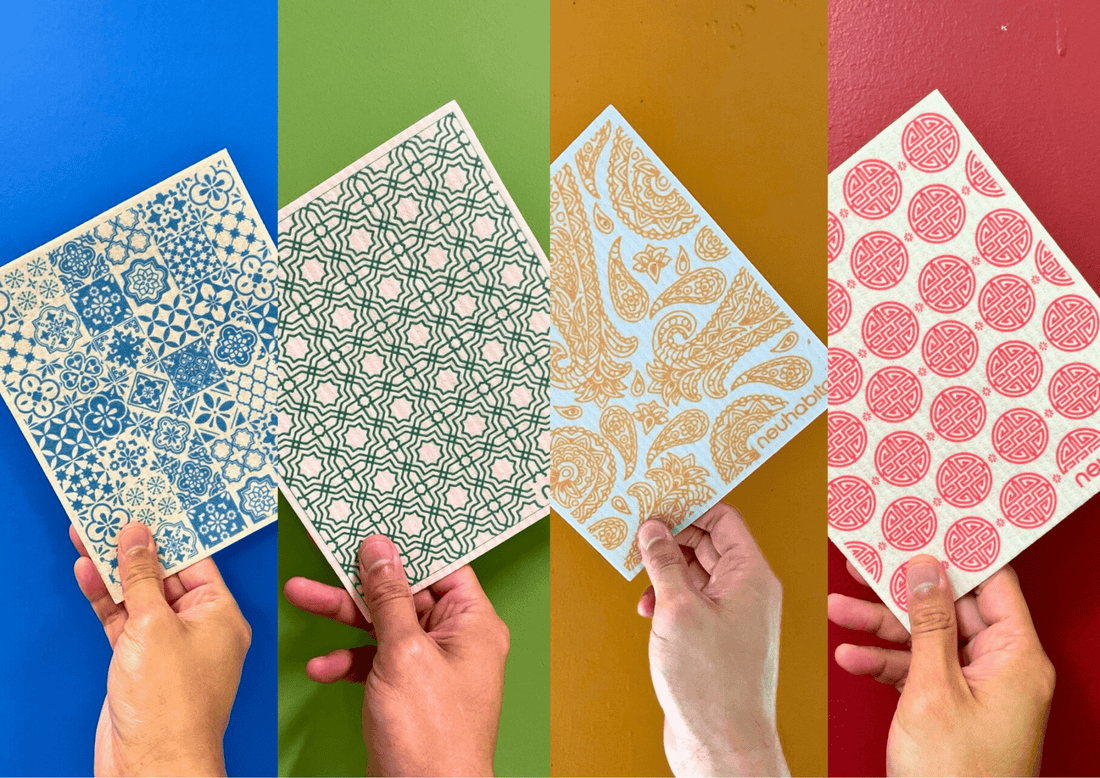

This year, as Singapore celebrates its 60th birthday, we decided to launch a collection of prints on our sponge cloths that best represents our country's cultural diversity. We explored and approached traditional art from Chinese, Muslim, Indian and Eurasian lenses, creating 4 designs/patterns that signify the 4 main ethnic groups in Singapore.

So what's an azulejo? The word azulejo is a singular term derived from the Arabic word "zellij" meaning "polished stone" where the original idea was to imitate Byzantine and Roman mosaics.

The earliest azulejos in the 13th century were panels of tile-mosaic known as alicatados in Spain and would later find its way onto precious altar cloths in Portugal, circa 16th to 18th century. With a vast history of more than 500 years, it's hardly a question of "should we include this style of art into our SG60 Collection?"

Azulejos' correlation with Eurasian culture can be found here in many of Singapore's historical buildings, such as churches, mosques, peranakan shophouses and The Eurasian Community House. These tiles have become an integral part of our country's architectural identity.

A brief history of inter-marriages between European settlers and locals gave rise to the Eurasians' vibrant amalgamation of Western and Eastern traditions in Singapore. As of 2020, there are about 18,000 Eurasians residing in Singapore. Most if not all of the azulejos or the "peranakan tiles" you've seen in Singapore have been inspired by the Portuguese or Spanish colonists and traders that settled in Southeast Asia.

The color selection of blue and white for the azulejos on our Swedish dishcloths are intentional. Since the early days of international trade, the europeans have been fascinated with the elegance and fine touch of Chinese porcelain. As porcelain was difficult to manufacture because it used an ingredient (Kaolin) that didn’t exist in Europe at the time, porcelain became an object of luxury due to its rarity and a symbol of wealth. During the 17th century, in an attempt to copy it, the Dutch began making tiles in the same blue and white tones as Chinese porcelain. The tiles pleased the Portuguese so much that massive imports were ordered from the Netherlands to decorate the Portuguese buildings and till this day, plenty of azulejos can still be found in a nice blue and white glaze.

Next, we created the islamic "girih". Pronounced as "gee-ree", are Islamic geometric patterns used in architecture and handicrafts, mostly consisting of interlaced strapwork patterns and angled symmetrical lines.

The earliest form of "girih" dates back around 1000CE, found on the frontispiece of a Quran manuscript in Baghdad. Then, in the 10th century a systematic investigation of geometric patterns was conducted by Persian mathematician and astronomer Abu al-Wafa' Buzjani in the House of Wisdom. In his treatise,"A Book on Those Geometric Constructions Which Are Necessary for a Craftsman", he explained the geometric structure and illustrates the methods of drawing polygons within other shapes (mostly circles) for craftsmen and artisans.

This book laid the groundwork for designing girih by explaining fundamental grammar for the construction of girih patterns.

A basic construction of girih would be based on hexagonal overlapping circles grid that can be drawn with compass and straight edge. Today, artisans using traditional techniques would utilize a pair of dividers to leave an incision mark on a paper sheet that has been left in the sun to make it brittle. Straight lines are drawn with a pencil and an unmarked straightedge. Girih patterns made this way are based on tessellations, tiling the plane with a unit cell and leaving no gaps.

While classical girih patterns (as seen in Persian or Ottoman architecture) are rare in Singapore’s context, Muslim architecture and fashion design are found to adopt geometric principles which are central to girih; symmetry, repetition, and sacred geometry. From the intricate geometric artwork on the domes, arches and, interior walls of the Sultan Mosque (Masjid Sultan) to the geometric motifs found on the wood carvings and perforated screens at the Malay Heritage Centre. These designs reflect the broader Islamic artistic vocabulary shared with girih patterns, emphasizing symmetry and mathematical precision.

Our color selection of green holds a certain significance to Muslim culture. Green color in Islam is often used to symbolize hope, prosperity, and eternity. Green is symbolic of the Prophet Muhammad, spiritual growth, and the beauty of nature. It is associated with the lush gardens of Jannah in the Holy Quran and is often used in Islamic flags and emblems.

Indians make up a 3rd of our racial construct in Singapore, and they possess a rich cultural background. In Indian culture, the paisley pattern, known as "Kalka", symbolizes life, eternity, and resilience, stemming from a blend of floral and cypress tree motifs, with the cypress tree representing immortality and the floral elements representing life and fertility.

The paisley motif began its humble beginnings as "boteh" or "buta," meaning "shrub" or "flower", which is described as a teardrop-shaped design that originated in Persia and became a popular motif in Indian block printing.

During the Mughal Empire (16th–19th century), Persian aesthetics profoundly shaped Indian art. Mughal emperors like Akbar invited Persian artisans and weavers to India, integrating the "boteh" into textiles, architecture, and manuscripts. This royal patronage cemented its status in elite and sacred contexts.

The motif was later renamed "ambi" (mango) or "kalka" (opened bud or petal), a symbol of prosperity, fertility, and divine favor in Hinduism. This rebranding made the design resonate with local cultural and spiritual values.

Furthermore, the paisley motif flourished in Kashmir’s pashmina shawl industry. Kashmiri artisans refined it into intricate "Kani" embroidery, creating luxury shawls coveted by Mughal nobility and later European elites. These shawls became a cultural emblem of Kashmir, blending Persian geometry with Indian craftsmanship.

Today, Indian artisans merged the "kalka" with local motifs like "bel" (vine) and "buta" (flower), creating a distinct Indo-Persian style. This fusion is evident in Mughal miniatures and "chikankari" embroidery.

The motif’s adaptability to symmetry, repetition, and flowing lines aligned with India’s love for intricate, organic patterns in art and textiles was the main reason why we wanted to feature this amazing pattern on our Swedish dishcloths. Because the paisley’s journey from Persia to India exemplifies "cultural osmosis", where foreign elements are absorbed, reinterpreted, and immortalized through local genius. Its enduring legacy lies in its ability to bridge diverse traditions, embody spiritual ideals, and adapt to changing times, making it a timeless symbol of India’s artistic and cultural pluralism.

The saffron color of our paisley pattern also holds a fair amount of significance in Indian culture. Saffron is a symbol of purity and renunciation of material life. Hence, saffron robes are worn by Hindu ascetics and is thus the most sacred color in Hinduism.

I personally grew up with Chinese icons. And one of these icons is the circular shaped Chinese character "shòu" which appears alot during Chinese Lunar New Year.

The character "寿" means longevity and is frequently represented in a circular form, which symbolizes unity, wholeness, and eternity, reflecting the cyclical nature of life.

We wanted to showcase the cultural connection of the "shòu" motifs in the form of Chinese lanterns because of the shared symbolism of circles and light in our SG60 Collection.

"寿" and traditional Chinese lanterns emphasize "roundness", which symbolizes unity, eternity, and completeness in Chinese culture. The circular "寿" mirrors the shape of lanterns, reinforcing the idea of unbroken blessings and cyclical prosperity. Intricate "寿" motifs integrated into lantern patterns, are often paired with other symbols like cranes, peaches, or bats (蝠, "fú" for "fortune") and can be found during the Lunar New Year; displayed in homes or even commercial venues.

In multicultural Singapore, this connection can be seen at festive events like the "River Hongbao Festival" (a major Lunar New Year event in Singapore), where giant lanterns featuring "寿" and other blessings light up Marina Bay, blending tradition with modernity.

The circular "寿" motif and Chinese lanterns are intertwined through shape, symbolism, and shared cultural narratives. Together, they embody a timeless wish for life to be as radiant and enduring as the light of a lantern. In festivals, art, and daily rituals, this pairing continues to illuminate the deep-rooted Chinese reverence for longevity and familial bonds, while adapting to Singapore’s unique social fabric and remains a vibrant part of the nation’s cultural identity.

Cultural diversity in Singapore is a precious gift that enriches our lives and broadens our perspectives. By embracing and celebrating our differences, we can create a more inclusive, compassionate, and vibrant world. We hope that our SG60 Collection will inspire and enrich your families and homes; by creating a beautiful tapestry of new stories, traditions, and experiences one sponge cloth at a time.